Historic North Fork cabin nominated for National Register

A Flathead County cabin, whose owner met an untimely demise over a legendary woman in 1932, is nominated for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places.

Wilhelm Axel Christian Kruse erected what is now known as the “Billy Kruse Cabin” in 1925. Born in Denmark in 1886, Billy emigrated to South Dakota initially. He moved to the North Fork of the Flathead, possibly to be with his brother John “Jack” Kruse, who served as district ranger for the Blackfeet National Forest at Coram from 1916 to 1919.

Billy Kruse was described as “possessing a medium height, stout build, brown hair and blue eyes,” according to National Register documents compiled by Lois Walker. But he allegedly also possessed a bad temper, especially when drinking.

Like the other single men in this rural area, Billy Kruse appears to have used his cabin as a base of operations, working outside the immediate area much of the time and returning between jobs.

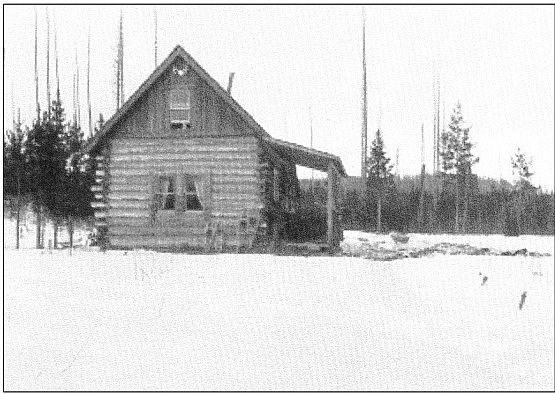

The single-pen cabin was constructed from locally available timber and boasts a small log addition that displays, as does the original cabin, well-crafted square notching on its corners. The cabin’s entry occurs on an eave wall, an uncommon location for many of the cabins in the North Fork area. The tight construction is evidence of the builders’ skills.

The original 16-by-18-foot cabin is built of hand-peeled larch logs stacked 13 high on the gable ends. Each log tends progressively smaller, except for one. It has 8-foot ceilings on the main floor, with a sturdy staircase leading to the second floor.

“The cabin stands as a testament to those who envisioned a place of their own in the rugged mountains of northwest Montana,” Walker notes in the nominating paperwork. “Many hoped that the land would sustain their way of life in this remote area but found it necessary to seek additional outside income.”

Success wasn’t guaranteed; Walker writes that of the 198 homesteads listed and entered by 1930 in the Blackfeet National Forest, 121 were abandoned or not used by that same year.

Loneliness was a constant companion for many of the Flathead bachelors. According to Tom Reynolds, a friend of Billy Kruse, in 1931 he became acquainted with a middle-aged woman from New York City through what Reynolds called, “a Hearts and Hands piece in some newspaper.” Though separated, Mary Powell was married with three children.

“Perhaps for financial reasons, or possibly because she was enamored with the idea of relocating to the remote Rocky Mountain West, she agreed to come live with Billy as a housekeeper/companion, bringing one of her daughters with her,” Walker wrote. “The end result of this relationship turned out to be very unfortunate.”

Author John Fraley laid out the situation in his book, “Rangers, Trappers, and Trailblazers.” He noted that Mary Powell and her daughter spent a fall and early winter, 1931-1932, with Kruse as housekeepers at his homestead and the situation seemed to be going well at first.

But Kruse was a sheepherder who also worked for the Forest Service and was gone often. Before leaving for one long sojourn, Fraley writes, Kruse asked his “buddy” and neighbor, Gustav “Ed” Peterson, to keep an eye on Powell, keep her supplied with wood, and generally help her if problems arose.

When Kruse was gone, Peterson turned his new two-story cabin over to the Powell women but remained in his nearby one-room cabin.

“When Billy finally got back to his cabin, he was stunned,” Fraley writes. “The cabin was cold and empty, and his mail order bride had apparently not lived there for a while.”

Kruse was furious that Powell had moved out of his house and started threatening to “settle with Mary” then with Peterson.

The feud boiled over on March 21, 1932.

“Billy bragged that he was a killer and that Ed was afraid of him,” Fraley wrote. “Finally, the group went to Ed’s house and Billy followed along, continuing to slug down alcohol. When they reached Ed’s house, Billy grew more and more ‘quarrelsome’ and became more drunk. Billy pulled out a firearm and ‘kept all of them at the point of a gun’ all evening.”

Kruse apparently fired a few random shots and threatened to burn down the house where Powell was staying before heading home.

The next morning, Peterson grabbed his .30-06 hunting rifle and a friend to see if the cabin remained standing. Meanwhile, Kruse stepped out a door and fired off a quick shot toward Peterson with his .22 rifle. It was no match for Peterson’s rifle, and he shot Kruse in the left bicep and chest.

Thinking Kruse was dead, Peterson left to notify the sheriff. But Kruse lingered for another 24 hours before succumbing to his wounds.

A coroner’s jury found that Peterson acted in self defense. On March 28, Kruse was laid to rest in the old Demersville Cemetery among other unmarked graves in the poor-house section.

Powell became a legendary figure in the North Fork, Walker wrote. She was known as “Madame Queen” and allegedly became a bootlegger, stayed with a variety of men, and eventually left the North Fork area.

The privately-owned cabin changed hands numerous times and is now a popular stop on history tours of the North Fork. It’s commonly called the Madame Queen Cabin.

The period of significance for the Billy Kruse Cabin begins when Kruse built the cabin in 1925 and ends when he ceased using the cabin due to his death. The rural setting remains mostly the same as when constructed, imparting the historic feeling and association of the construction period.

Interior modifications made it more hospitable but were made with sensitivity to the character and materials of the cabin, the nomination form notes.

“… the Billy Kruse Cabin represents the construction of choice in remote and forested areas of western Montana during the state’s territorial period and into the twentieth century,” Walker wrote in the nomination form. “Well preserved historic log cabins, while still found, are becoming increasingly scarce with the passing years with many replaced by newer log structures.

“It retains a high degree of integrity and stands as a fine example of simple, yet well-constructed log building that continues to serve succeeding generations.”